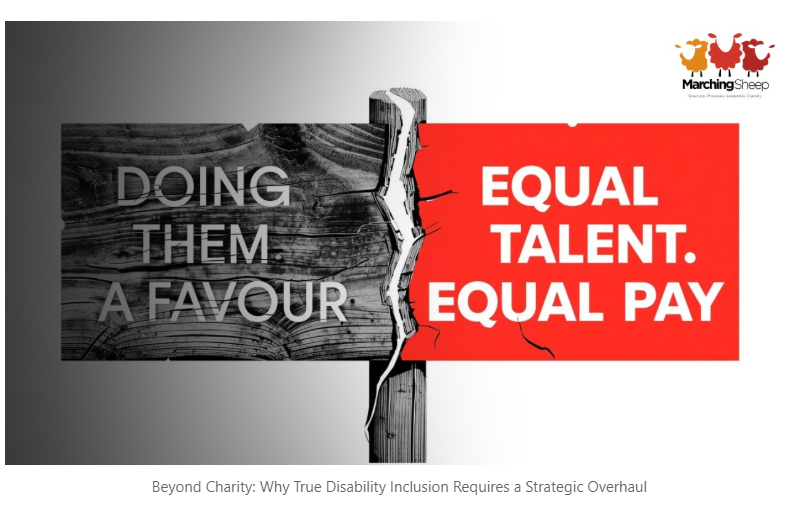

They said, “We are doing them a favour by hiring them, why do we have to pay?”

Our PwD recruitment team repeated the words of a talent acquisition lead of a leading IT company. I was taken aback, slightly irritated, not very surprised.

The conversation around hiring Persons with Disabilities (PwD) has, for too long, been viewed as charity, CSR, good to do, something driven primarily by NGOs and foundations, and adopted by organisations as a well-intentioned reputation building activity. The notion that companies are “doing a favour” by considering PwD candidates is not just patronising; it is a significant barrier to building genuinely inclusive culture and diverse and high-performing teams.

Placing talented PwD candidates should not be an uphill task, but it often is because many organisations fail to recognise that this is a strategic business imperative, not a corporate social responsibility (CSR) checkbox. The difficulty arises from outdated stereotypes, assumptions about productivity, capability, education and ambition of Persons with disability. inefficient processes, and a lack of empowerment within the HR function itself.

1. The End of the “Favour” Narrative: A Mutually Beneficial Partnership

The first mindset that needs dismantling is the charity model. When a company hires a PwD candidate, it is not a one-sided act of benevolence. The employer gains access to a vast, often overlooked pool of talent that brings unique problem-solving skills, resilience, and diverse perspectives crucial for innovation. The candidate, in turn, gains an opportunity with an organisation that is, or is committed to becoming, truly inclusive. This is a symbiotic relationship. An organisation intentionally building ramps, both physical and procedural, signals a modern, adaptable, and empathetic culture attractive to ‘all’ top talent, not just PwD. The uphill battle begins when companies approach this as a concession rather than a competitive advantage in the war for talent.

2. Meritocracy and Compensation: Disability ≠ Lower Productivity

A pervasive and damaging myth is that disability inherently correlates with lower productivity or an inability to meet Key Result Areas (KRAs). This unconscious (and sometimes conscious) bias is a major reason for the reluctance in hiring and for offering lower Compensation and Total Cost (CTC) packages. This assumption is not only incorrect but ethically wrong. A candidate’s disability may require reasonable accommodations, a screen reader for a visually impaired employee, a flexible schedule for someone with a chronic condition but these are tools, not indicators of diminished capability and productivity. The core skills, qualifications, and experience are what determine the role and its corresponding salary. Offering a lower CTC to a PwD candidate for the same role is discriminatory and instantly devalues the talent the company claims to seek. True inclusion means evaluating candidates on their merit and compensating them fairly for the value they bring.

3. The Pace of Modern Hiring: Respecting the Candidate’s Time

In today’s fast-paced job market, top candidates, regardless of disability, are not going to be waiting around for weeks. A protracted hiring process, where candidates are left hanging for weeks or months between interview rounds, is a recipe for losing the best people. This is especially critical for PwD candidates who may have faced repeated rejection and are highly attuned to signals of a company’s genuine commitment. An inefficient process signals disorganisation, indecision, and a lack of respect for the candidate’s time and other opportunities. If an organisation is serious about inclusion, it must streamline its hiring timeline. Speedy, transparent communication is not a special accommodation; it is a hallmark of a professional and respectful talent acquisition strategy.

4. The Criticality of Constructive Feedback

The silence that often follows a rejection is deafening and damaging. For PwD candidates, who may be navigating a system fraught with unspoken biases, the absence of constructive feedback widens an already significant trust deficit. A generic “we decided to move forward with another candidate” offers no path for growth and reinforces feelings of exclusion. Providing specific, actionable feedback focused on skills or experience gaps, not the disability is essential. It demonstrates respect for the candidate’s effort and investment in the process. This practice builds a positive employer brand, even among those not selected, and fosters a reputation as a company that values growth and transparency.

5. Empowering HR as a Strategic Partner, Not a Processor

Finally, the uphill task persists because Talent Acquisition (TA) and HR teams are often not empowered as strategic decision-makers. They are frequently seen as administrators who simply execute the wishes of hiring managers. For inclusion to work, this must change. HR must have the mandate and the skills to sensitise hiring managers. This includes training on inclusive interviewing techniques, recognising and mitigating unconscious bias, and making swift, collaborative decisions. HR should be the custodian of the inclusive hiring strategy, equipped to challenge hiring managers when biases emerge and to advocate for candidates based on merit and potential, not just familiar profiles.

The challenge of placing PwD candidates is not inherent to the candidates themselves, but to the systems and mindsets of the employers. The path forward requires a fundamental shift: from charity to strategy, from assumption to evidence-based evaluation, from sluggish bureaucracy to agile respect, from opaque silence to constructive dialogue, and from a compliant HR function to an empowered, strategic partner. When organisations make this shift, they will find that what seemed like an uphill task was merely the path to building a stronger, more innovative, and truly inclusive workforce.

Link – https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/beyond-charity-why-true-disability-inclusion-requires-sonica-hu8qc